Due to some of the comments on a

previous post I thought I could help lay a foundation for discussion by giving a crash course in everyday philosophy (kind of like a crash course in everyday physics, but for ideas instead of physics). The actual debate is much more complex, but for our purposes we can use the simplified form of the debate. This might be a little long, but bear with me. To understand some of what I am talking about it may be necessary

to read the post and comments that prompted this post. It may be a bit of a read, but it may make reading this a little easier to understand what I am talking about.

Part of the reason why the previous post elicited so many comments was that it, unintentionally, hit on a major philosophical debate, that of the distinction between epistemological realism and epistemological idealism, which has also been classed as a difference between

objectivism and subjectivism, and is related to the debate between empiricism and rationalism.

First I will explain what I mean by 'epistemological'. Epistemology is the study of how we know things. That's it, very simple. So 'epistemological' indicates a way in which we know something, either through realism or idealism. Now I will explain the difference between, and related ideas of, epistemological realism and epistemological idealism. After that I will discuss why the distinction is important and how it comes up in everyday conversations using examples from the comments in the

previously mentioned post.

In the simplest sense epistemological realism is the idea that observable characteristics exist in the observed object, independent of the observer. Likewise epistemological idealism is the idea that the characteristics exist in the mind of the observer independent of the object. So why is this difference important and where does it come up?

You may have heard (haha) the example of "If a tree falls in a forest does it make a sound?" Someone who is a strict epistemological idealist will say, no, because no one is there to observe the tree falling to interpret what happened as making a sound and thus it cannot create a "sound". But someone who is a strict epistemological realist will say, yes, because sound is just pressure waves in the air and there does not have to be an observer in order to make a "sound". The reason why this simple example presents a problem to many people is because they are not strict realists or strict idealists. Because they personally have a mixture of views they usually settle on the conclusion, "Well it depends." or "I can see how it could be either way." or "Stop bothering me with stupid questions." (as a side note, the people who respond, "It depends on what you are talking about. If you when you say "sound" you mean the mental process that recognizes it as such, then no there was no sound. But if you mean pressure waves in the air when you say "sound" then, yes there was a sound made." The people that respond like this are called

Pragmatists.) But a strict realist or a strict idealist will give a definitive yes or no answer to the question (I am, for the most part, a strict realist, with a tempering of pragmatism, as are many scientists. I will discuss this further down.).

Furthermore, epistemological realism, also called

objectivism (not to be confused with

Objectivism, which is the philosophy taught by

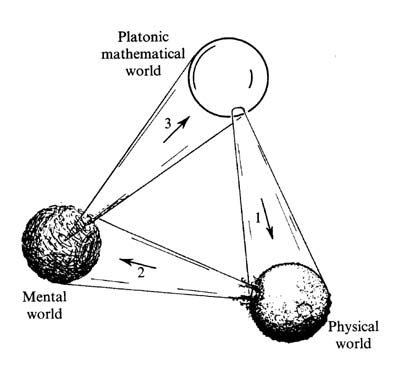

Ayn Rand, though they are definitely related), is dominated by two schools of thought, that of Platonic objectivism (other wise known as the

Theory of Forms) and Aristotelian objectivism (of which

Ayn Rand's Objectivism is a modern adaptation of). Platonic objectivism assumes that the highest form of reality is that of the Forms, which cannot be accessed through our senses, but only through reason and rational thought. Thus objective reality is grounded in our rational thoughts. This way of thinking (or the objections to it) has dominated Western Philosophy and has been the basis of the philosophical systems of

St. Augustine,

Descartes,

Kant and many more philosophers. This dominance has been so complete that it prompted

Alfred North Whitehead to say,

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. I do not mean the systematic scheme of thought which scholars have doubtfully extracted from his writings. I allude to the wealth of general ideas scattered through them.

This dominance of Platonic thought worked its way into Christianity through St. Augustine, who explicitly stated that in matters where the Bible was silent, an appeal to philosophers (Plato) could be used. This union is generally referred to as the

Hellenization of Christianity. This brought many of the Platonic ideas of God into Christianity, including things like God has neither body, parts nor passions, among many other ideas regarding the omnipotence and omniscience of God.

To recap, the major distinctions here include epistemological idealism, which holds that any characteristics that can be known of an object exist

only in the mind of the observer. Epistemological realism holds that what is knowable exists in the thing being observed and is independent of the observer. Epistemological realism can roughly be sub-divided into two categories, namely Platonic rationalism and Aristotelian empiricism, the former being that the objective reality can only be accessed by the mind, but it is still objective, and that what is learned by the senses is dependent on the rational thought of the observer. The latter holds that the senses have primacy in determining the objectivity of reality, with our rational thoughts being subject to our experience.

The question is now, is there an application beyond simple (or silly) philosophical brain teasers and esoteric debates between old dead guys? Yes! there is. As it turns out, these very ideas are what prompted Nick's post and the string of comments afterwards. Let us take a look at some of the comments and find out what ideas are kinking around. Keep in mind that it is very rare for one person to be a strict realist (meaning they only express realist ideas) or a strict idealist. Usually people express some combination of the two. A number of people are idealists when it comes to God (both believers and atheists alike) but are strict realists when they have to go to the store and buy milk. Also as a note, science is strongly in the camp of epistemological realism, with a mixture of Platonic rationalism and Aristotelian empiricism, though usually with a strong emphasis on the empiricism.

First, "advocacy of an unverified and unverifiable hypothesis such as God of any book is myopic." (

link) The fundamental assumption here is that God, as an unverified and unverifiable hypothesis, is only known through the experience of an individual. Thus this is a statement that God is known through epistemological idealism. Because "God" is a personal thing, it is not something that can be transfered from person to person, and hence is "unverifiable", i.e. not objective. This viewpoint is actually fairly common among believers (or the faithful). As one grad student I know once told me, his experience with God was a personal experience that he had had and readily recognized that he could no more prove his belief and knowledge of God to another person than he could prove the existence of his own thoughts.

One of the results of this way of thinking is that when confronted with the dilemma of having God known through idealism, but science largely through realism, the standard response is to say that there are limits to knowledge through epistemological realism and that the knowledge of that which pertains to God is of a different realm or level. Thus the statement, "How do we describe our “limits of knowledge”? By beliefs!" (

link) This expresses the idea that all that can be known through epistemological realism (i.e. science in general) is limited in some way and when we reach that limit we declare that then begins our faith, and we move into the realm of epistemological idealism.

The main criticism of this approach is that "religious "apologists" ... frame a "hypothetical" god in such a way to render it unprovable by modern methods." (

link) Because the belief in God retreats into the realm of epistemological idealism, it is assumed that "God" has become unverifiable and unprovable, and many people of faith will admit this. Those that find this approach towards God to be unacceptable insist that "the existence of god is a question that can, in principle, be answered scientifically." (

link) This statement is an assertion that all things, God included, are subject to epistemological realism and must therefore satisfy the demands of an objective reality.

The difficulty here is that the usual approach of Christianity is to use Platonic rationalism. So while Christian theologians and

apologists (here the term apologist is a very apt term, because (quoting Wikipedia) "

Apologetics (from Greek απολογία, "speaking in defense") is the discipline of defending a position (usually religious) through the systematic use of reason.") such as

C. S. Lewis,

St. Augustine and

many others are very good at rationally explaining their faith, they are subject to all the debates and problems of Platonic philosophy.

Previously I mentioned that when believers reach the limit of epistemological realism they then move into epistemological idealism and make God a subjective reality. But for those of us who stay firmly rooted in epistemological realism and insist on God being an objective reality, we run into the problem of the limits of Platonic rationalism and this usually prompts statements like this, "I admittedly can *never* prove [God] exists as much as give reasons to believe He is a viable option." (

link) This is a classic example of recognizing the limits of Platonic rationalism, while still insisting on an epistemological realism in regards to God. Thus, by saying this Joe is keeping within the realm of realism without reverting to a idealist argument. The reason why statements like this are still scientifically consistent (i.e. still epistemologically realist) is because of things like Gödel's incompleteness theorem, and Wittgenstein's private language argument. These arguments are summed up in statements like this, "The Venn diagram of *true* things is larger than the Venn diagram of things that can be proven or refuted using science." and "A worldview restricted only to science is limiting." (

link). This particular approach still relies on the "different realms" argument for science and theology, but insists on God being objective, even if He falls outside the realms of logic.

To sum up, I find that most common explanations and arguments about God assume that He falls within the realm of epistemological idealism as a personal experience, which results in the criticism that God is unverifiable and unprovable because He is a subjective experience. Which leads to the assertion that belief and faith are a private thing and must be kept private. Hence the statement, "Here is the crux of the problem: Priest can pray to his heart content; he can not ask others to join him, if he wants to be a scientist." (

link) Because faith is a private (subjective, idealistic) thing then to insist that others share the same experience (be objective about it) is rightly thought of as a logical inconsistency (hence the, "So he is a oxymoron.").

But for those of us who consider God to be within the realm of epistemological realism, then it is not logically inconsistent to be a religious scientist. The debate then moves into the realm of whether or not it is rational to believe in God as an objective reality. The common criticisms at this point are either a rational (philosophical) attempt to disprove the existence of God (a number of serious arguments against God are of this type. See, Ayn Rand, Nietzsche, Dawkins and other well known atheists), or rely on a more agnostic argument insisting that they have never had an experience with God and therefore cannot rationally accept His existence, which I admit makes perfect sense.

I hope this explanation helps the conversation and gives us a basis for discussion. I also hope that those that read this can see how this seemingly

highfalutin explanation actually relates to everyday things. While the point of this post was not to convince anyone one way or the other, I hope it will help people have a better grasp on what is going on and understand why people respond the way they do.

Keep in mind that many people use a combination of realism and idealism in their lives and in how they understand the world and do not strictly hold to one or the other. Also, even for the realists they use a combination of rationalism and empiricism, and usually do not take the time to set a clear distinction. Thus it is a rare thing that all these ideas can be brought together in a single conversation, which is why I took the time to point them out and write this post.

For those that are interested in my own personal views: I am a epistemological realist of the Aristotelian empiricism persuasion. This means that I firmly know that God can be known objectively, but that logical or rational arguments are insufficient (but not useless) in communicating knowledge about God. This means that knowledge of God must

first be gained independently and personally, but after that knowledge is gained it is subject to the system of objective checks and balances, meaning before I can claim experience with God in a rational way, it must be independently verified by the personal experiences of others. This verification happens through a rational, logical discourse, which of necessity cannot happen until those involved have had similar experiences on which to base their conversation. This does not mean a conversation cannot take place, but full knowledge will only come through personal experience.