Previously I posted on the "conflict" between science and religion. A critical distinction that I made in that post was the difference between the Platonic and Aristotelian world views. At the time I did not offer an in depth explanation of what constituted a Platonic or Aristotelian world view partly because they are rather difficult (i.e. would take several books) to explain. But not to leave those who are interested with absolutely no explanation I will attempt to give a brief explanation of the fundamentals of both. [Editorial Note: When I am giving an explanation I will often include another word in parentheses after a word which has a technical philosophical definition. The word in parentheses is a more colloquial (common) word used in the same context. Both words are interchangeable but I felt that more than one word was needed to get an idea across while still using the "correct" philosophical language (words). If you find it annoying, sorry. I can't think of a better way of doing it.]

On a basic level a Platonic world view carries with it a fundamental distrust of the material (observable) world. An Aristotelian world view fundamentally assumes that all knowledge comes from the observable world (universe). Note that these ideas are not opposite nor are they even mutually exclusive. But they are two approaches to the same thing, how we know and interact with the world.

In my previous post I implied that the Platonic world view was the root of many problems, and while it is, I should qualify that with an explanation. If not considered rightly a Platonic world view can lead to many philosophical (intellectual) problems. By way of explanation I will use a simple analogy, specifically tailored to my assumed audience, those who read this blog. This analogy will not work for everyone.

When we are first learning physics the standard approach is to learn physics with a heavy emphasis on the algebra involved. This means that the equations are given to us in a standard form, from which we work problems and (hopefully) come to an understanding of the physical principles involved. When we have passed this step and we have achieved a certain level of understanding, generally one then returns to the basic physical principles, and relearns them but now with an emphasis on deriving the equations and solving more complex problems using calculus instead of algebra. This allows us to solve problems and answer questions that were impossible before. Problems such as including wind resistance in projectile motion problems. The underlying physical principles have not changed, just our approach to the problem.

This different approach fundamentally assumes that the world is not as "simple" and "easy" to deal with as is usually presented in introductory physics classes (i.e. the world is not made up of spherical cows). While things may be more difficult, and require more training and experience, the outcome allows more understanding and insight.

For all simple cases there is no difference between an algebra based approached to physics and a calculus based approach. As a matter of fact if we tried to solve every basic physics problem by first writing down the Lagrangian for the system and then finding the equations of motion we would never have time to finish solving all of the simplest problems. So in some cases it may even be advantageous to use an algebra based approach than to use a calculus based approach. But if we do this we must realize that we are using a simplification and to not get bogged down in the potential shortcomings of the purely algebra based approach.

Now relating this back to the Platonic and Aristotelian world views, the Platonic approach recognizes that the world is very messy and is not "ideal", meaning that it cannot easily be reduced down to simple, easily solvable problems. There is no problem with this, as this is also the view taken by an Aristotelian world view. But the problem arises when someone who holds to a Platonic world view begins to think that the universe is actually made up of spherical cows (i.e. atoms are "hard" and perfectly spherical, all things can be considered to be point particles, forces behave exactly like 1/r^2 laws etc.). So the problem is not that spherical cows (simplifications) are used to solve (comprehend) problems (reality) but when we begin to actually think that the universe is made up of spherical cows (ideal, according to our understanding) we run in to intellectual (philosophical) problems (mistakes).

You may be thinking, "What in the world is he talking about? How does this relate to anything important? And does this have any bearing on how the world, and our society works?" Well to answer those questions let me give a few examples.

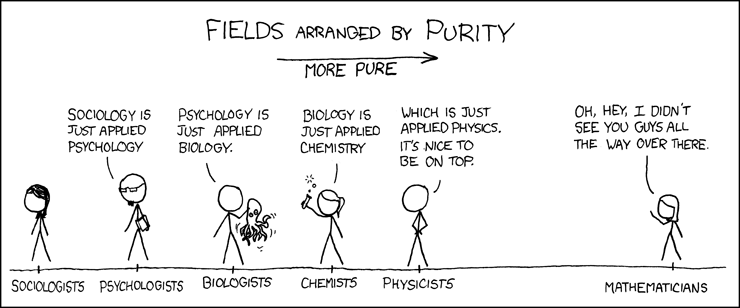

First, recently there was a post on this blog that included this comic:

Without knowing it (or maybe he did) by posting this comic Joe was showcasing the Platonic world view (and one of the problems with it). Essentially the XKCD comic expresses the idea that the further away from reality we move, the more "ideal" or "pure" we are getting. Implicit in this argument is the assumption that in order to understand the world we must move away from all the "messy" stuff and move in the the realm of pure thought. Only then can we begin to understand anything. It is interesting to note that in seven short comments attached to that post the Platonic world view was debated, debunked and rejected in favor of the Aristotelian world view (and Clark Goble even managed to include both Heidegger's and Wittgenstein's arguments against the Platonic nature of language, impressive. And Bill, John Locke and John Stuart Mill would be proud, though many philosophers would try to lynch you for it).

So other than comics where does any of this show up? Again I need to emphasise that the basis for the Platonic world view is a fundamental distrust of reality (observation, sensations). This fundamental distrust of reality leads to all kinds of weird wacky things, like this gem that my wife came across one day. On a basic level the Platonic (or Platonic like) world view leads people to assume that in order to learn anything "real" or of value, they must disassociate themselves with reality (the physical world). This was the motivation behind the drive to use "experimental drugs", such as LSD, in order to experience things that could not be "experienced" in the physical world (this was explained to me by a philosophy student who "had friends that did drugs").

There are other implications to this but to sum up it, is enough to say that even though the Platonic and Aristotelian approaches to the world both consider the physical world to be "messy" at first, the Platonic approach feels that the "messiness" prevents the discovery of the world and thus in the ideal case we must remove the influences of all the "messy" stuff from reality, including our senses and anything that has to do with our "physical" bodies. The Aristotelian approach recognizes that the world is difficult, and while simplifications (math, equations, words, language) can be used to make it easier, the simplifications are just that, a simplification and not an ideal. Thus a Platonic approach demands that new knowledge comes from the ideal world (Plato's world of Forms), while on the other hand the Aristotelian approach assumes that knowledge comes from observation (sensation) of the physical world, and is verified again by observation. All knowledge according to the Platonic approach, by definition, is not verifiable in the Aristotelian sense, but is entirely determined by whether or not one can "think correctly" about it.

So how does this relate to the original motivation for this post involving the "conflict" between science and religion? On a fundamental level science takes an Aristotelian approach to how we learn and find out things about the universe. It asks, "What do we observe and how can we explain what we observe?" While science (and physics in particular) takes an Aristotelian approach, it is not exclusive. We still see a substantial amount of Platonic thought in science, but it is not as common as it is in other fields of research (Math is one that is substantially Platonic).

Perhaps the most prominent place Platonic thought shows up is in religion. I should emphasize that there is nothing about religion that demands Platonic thought, but at times it does seem rather conducive to Platonic thought as it mostly deals with things that are not (obviously) related to the five senses (I put the "obviously" in there because I disagree with that assertion). But if we are working under a Platonic world view then it makes sense that if one considers the mental or the abstract (the Platonic Forms) to be the most pure and perfect then that is where one would consider their God to be. This leads to the argument that God does not partake of the physical world and does not have any part in it other than being the unmoved mover (important note, there is an important distinction here between having an unmoved mover, as was Aristotle's concept, and thinking of God as the unmoved mover). In the end religion (and other "intellectual" fields, such as philosophy and math) became dominated by Platonic thought, while Aristotelian thought dominated science. Again this was not an exclusive domination (nor even correct) but that is the way it stands today in our society.

This causes problems when the question is asked, "Can you prove that God exists?" A Platonist would respond with a philosophical argument for the existence of God, an Aristotelian would respond with a demonstration of the existence of God. In the first case scientists (who are largely Aristotelian in their approach to knowledge) would reject the arguments as invalid because in order to "prove" anything according to science it must be demonstrated (mathematical proof does not count, it has to be demonstrated by experiment, see string theory). Thus the requirements for "proof" are fundamentally different for the Platonic approach and the Aristotelian approach, and because 80-90% of religion takes a Platonic approach, the tendency of scientists is to reject religion as invalid. Unfortunately this rejection first assumes that religion is fundamentally Platonic, and that any approach to it must first be Platonic (including a "scientific" approach).

This difficulty goes away if an Aristotelian approach is taken with respect to both science and religion. In other words it must be assumed that the same modes of knowing can be used for both, which depending on your views of religion (or science, or both) may be an issue. But if the same method is used for both then all apparent difficulties go away (interesting note: it works both ways, if a Platonic approach is taken in both cases then there is no conflict, but as long as a different approach is taken for either science or religion then there will be a conflict).

So now after this long explanation I will return to what I started out by saying:

On a basic level a Platonic world view carries with it a fundamental distrust of the material (observable) world. An Aristotelian world view fundamentally assumes that all knowledge comes from the observable world (universe). Note that these ideas are not opposite nor are they even mutually exclusive. But they are two approaches to the same thing, how we know and interact with the world.

The problem comes when we take the Platonic distrust of the material world to the point that we think that the material world inhibits our understanding. This is in opposition to the Aristotelian view, which is that even though the observable world may be difficult to understand it is the basis of our knowledge and our understanding and we cannot reject it as the fundamental source of knowledge.

Quantumleap42,

ReplyDeleteVery interesting to read and I enjoyed many of your points, especially discussing problems that arise when you mix and match various things. I really agree this is all too true.

1. I will say, I actually have a "whatever works" mentality about these world views. I think progress has been gained by exercising both these views.

On one hand:

The classic example is Einstein: he has several quotes admitting many of his theories came from asking himself how the thought the world should be. For example, he had no evidence that space was curved, but had a aesthetic believe that equations should be tensorial and conform to philosophical ideas such as Mach's principle. Then, from aesthetic reasons alone, he maintained GR had to be the form it is in. (Leading to curved space.)

You could argue it required this Platonic view for Einstein to formulate GR.

On the other hand:

Thank heavens people have demanded that we don't just accept Einstein's ideas because of their aesthetic appeal. We are much better off rigorously testing every scientific theory no matter how aesthetically pleasing it is.

So, the "ideas must comply with observed reality" mentality also has been very helpful to society. Making claims without demanding proof can be dangerous.

So again, to me "whatever works" and leads to real progress is helpful. (I'll let you define progress. :) )

2. I'm glad the comic post and further discussion helped you this post. Who knew I was setting myself up? :)

I think it is a good idea to try to use as much as possible common words, because relating about philosophy should not be something in order to give a headache to the others. Otherwise I think those who are taking drugs are a bit abusing, because generally the best thinkers relate about the fact that in order to have some clear thoughts it is better to not take any drug.

ReplyDeleteAwesome post! I learned a ton. Here are some questions/thoughts.

ReplyDeleteIt seems to me a necessity that these two world views will collide. That is, I don't see how one could take a Platonic world view and apply it to both science and religion. At some point the data will contradict the thinking. Won't it?

I guess I think it is a psychological trait that humans possess that we expect our views of the world to align with what we observe, be able to use those views to predict future events, and that they are repeatable. Whatever view you espouse, if your observations don't match your hypothesis, you either change the hypothesis or reject the observations. Either way, cognitive dissonance will occur and life will get uncomfortable.

In Mormonism, I don't think things are any different. Members of the church get a spiritual witness that the church is true. I suspect that for most people they accept this spiritual witness because they find it a valid mechanism for determining truth. Why? I postulate that it is because they have tried spiritual witnesses in the past, and find them to predict future outcomes (promptings by the HG that lead disaster avoidance), align with observable reality (leaders of the church don't let us get too far off unlike in the early days of Mormonism), and repeatable (hindsight is always 20/20 when deciding if something was reliable).

I'm not being critical of Mormons, just pointing out that I think, at least in Mormonism, we use our spiritual witnesses (a seemingly fundamentally Platonic mechanism) in a very Aristotelian way.

The only other thought I have is that at some level there is some conflict for a great many people. Either they doubt their spiritual witness, or the evidence for the claims of their particular religion doesn't hold up in their eyes, or... In my mind this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of religion vs. the purpose of science, but admittedly religion has strayed (and continues to in many areas) into areas which theology should not go.

Joe,

ReplyDeleteAt a certain level there is no difference between the two world views, the real test is how you consider something proved. So while Einstein may have been motivated by a desire for elegance, and conformity to a certain idea, his ideas would have meant nothing if they were disproved by experiment. That is, his ideas, no matter how "elegant" or how well they conformed to certain ideas, wold have been no better than any other now defunct theory of gravity, if it weren't for the critical proof of experiment.

I find that when ever I try to talk to people about these ideas one of the first responses is that it appears that in the Aristotelian world view, reason, thought experiments, and logical proofs cannot be used. This is not the case. The difference is that in the Aristotelian world view all the reason, thought experiments and logic must ultimately be verified by observation. The Platonic world view does not demand this.

jmb275,

"I don't see how one could take a Platonic world view and apply it to both science and religion. At some point the data will contradict the thinking. Won't it?"

Yes, but that doesn't stop people. This is one of the greatest free will arguments, because people cannot be forced to think of the world in a particular way proves that we are free to think of the world in any way we see fit. That does not guarantee we are correct though, it's just means we are free to mess up.

As for Mormons, we have a rather Aristotelian outlook in how we approach religion. While this may seem like a contradiction, it is only a contradiction if you first assume that religion (God, the Holy Ghost and spiritual feelings) are inherently Platonic. The problem with this is that if we view religion in this way then we run into the problem of Wittgenstein's beetle (a very interesting insight).

Plato= Communism, fascism.

ReplyDeleteAristotelian= Individual rights, freedom, science.

Hi I think what the comic illustrates is perfectly valid. Each stage is a Continuum of Knowledge. If you notice, each stage is not exclusive to the previous but inclusive of its prior. Plato's cave is not a rejection of empirical reality, but that each stage is to represent a continuum of understanding to put one on the Road to Reality. In other words, you have to be 'cooking with gas' at each point, in order to move up to the next stage of knowledge. The shadows on the wall of the cave represent the human mind's first grasp of a material object, but if there is no 'shadow' (no empirical reality) than there is nothing to observe. In essence, the Platonic science always starts with material reality in it's observation and analysis. The forms are only the last stage of mathematics, which results in pure intuition. The forms are not isolated 'things' apart from and prior to the 'things' that they constitutionally 'cause', and all forms are an interweaving fabric which constitute mutual differentiation. On this gloss, no form can be contextualized apart from another.

ReplyDeletePlato's political theory is not modern communism and fascism. It's more or less the Pharonic Order Ma'at (without a dynasty) devoid of any reward of wealth, since they sought solely justice and knowledge. What Plato imagines is extremely high standards of qualifications for his "guardian philosophers" and the philosopher-king, and it is basically a reworked Egyptian state. Right, wrong, or indifferent on Plato nothing in the West has come close to a reproduction of his ideal. Plato saw Egypt as somewhere between laissez-faire Democratic Athens and the Ideal state (closer to the ideal state for Plato). And I think that the "democratic" republic of the US is somewhere between Athens and Egypt, since those were the two influeces of the Founding Fathers.

Established transportation infrasctructure for a

ReplyDeleteplethora of lifestlye, dining and entertainment.the interlace condo (theinterlacecondo.sg)

Thank you...this was a very helpful introduction

ReplyDeleteOne question that came to mind is that in a place like the US, most citizens gain knowledge from observation of media, the media (for the most part) makes the world seem almost unintelligible. What if the platonic view is a way to always seek the purest form of information rather than what is observed first? I think Plato meant to make people always seek the best and most qualified source of knowledge, while Aristotle's view allows mass deception based on a monopoly on what is observed. Plato's view allows one to choose their view based off of inner reasoning of what is good or bad. Your piece has inspired some great thought for myself and I thank you, any feedback would be appreciated.

ReplyDeleteGreat read thaanks

ReplyDelete